Newfoundland is swimming in mariner folklore, but no other story about a run-in with Architeuthis dux captivates audiences more than the Squires-Picot sighting on Oct. 26, 1873.

Two fishermen and a boy were fishing in the tickle near Bell Island, just a few miles north of St. John’s, when they encounter what was then called a “Devil Fish”.

One can imagine Daniel Squires and Theophilus Picot made like the ancient mariner of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s famous poem whenever they recounted their encounter. But they had proof of the failed fishing expedition: a severed tentacle.

Picot’s 12-year-old son Tom had detached the appendage from the squid with a hatchet, saving the trio and also solidifying their tale.

But … in other accounts, it seems that Theophilus Picot was the only person aboard the boat.

As improbable as it may sound, retired researcher with Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Earl Dawe, admitted that it did indeed happen. And the chopped-off limb can be found in the St. John’s museum.

“That’s no fabrication,” he said, during a March 2020 phone conversation. “In terms of giant squid encounters for the small size that this little island of Newfoundland is, there’s been quite a lot of discoveries of giant squid.”

But usually the animals are remnants of a past life. Carcasses wash ashore or are found like flotsam bobbing on the ocean.

“I, for a long while, thought that it was just a legend too,” Dawe admitted. “I have many old photographs of in the 1800s of people staring in amazement at these dead creatures on the beach.”

Dawe admitted that there were many sightings of giant squid during the 1870s.

There are other instances, such as British journalist F.T. Bullen’s sighting aboard the whaling ship Cachelot in 1875. The battle between two foes, the sperm whale and giant squid, unfurled before him as he watched through binoculars.

On Nov. 2, 1878, Thimble’s Tickle, now Glover’s Harbour, had the heaviest specimen ever recorded wash onto its shores. The carcass still holds the Guinness Book of World Records title, with a mantle length of 6.1 metres (20 ft) and tentacles measuring 10.7 m (35 ft) for a total length of 16.8 m (55 ft).

A perfect environment for giant squid?

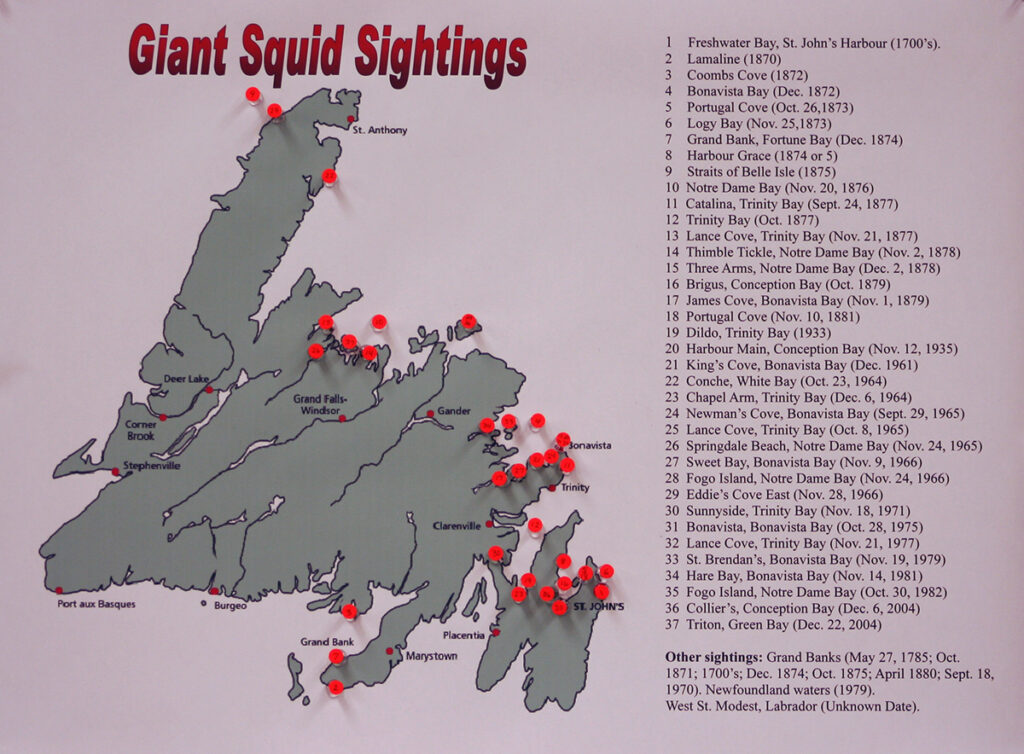

A map shows all the sightings of a giant squid — dead or alive — around Newfoundland’s coastline. The lead photo above is from the 1933 Dildo, Newfoundland discovery.

Dawe spent the early portion of his career in 1980 studying squid, but mostly the shortfin variety. He was later shifted over to snow crab in 1986 at the behest of his superiors, but squid continue to hold onto his attention.

“We had an incredible period just before and after I was hired from 1975 to 1982,” he recalled, adding 193,000 tonnes of squid were caught in mostly Canadian waters in 1979.

Then the squid disappeared by 1983, or at least not at that same level of abundance. There are two species on the East Coast: the shortfin squid and the longfin squid. The former live deeper in the ocean while the latter has a coastal habitat.

In 2007, he did two papers explaining that the abundance of squid is closely tied to oceanographic conditions.

“Their abundance oscillates in opposition to each other,” Dawe said. “When one’s (numbers) are up, the other is down, and this is all regulated by the environment.”

The gulf stream plays a big role in both of the two species’ lives. Architeuthis, however, is not considered to be a continental shelf dweller. They typically inhabit the midnight zone of the ocean depths.

“When they’re discovered in Newfoundland, it’s at times when they stray from their normal deep water, cold water, dark habitat, up the slope and die for some reason, and then the Labrador current takes the floating animals and pitches them up on the beach,” he said.

Most of the animals discovered are female, and their mantle length can be up to 3.35 metres (11 ft.), with an additional 12 metres (40 ft.) for the head and tentacles. Squids are sexually dimorphic, with the males being about one-third of the size of the females.

The beast of lore

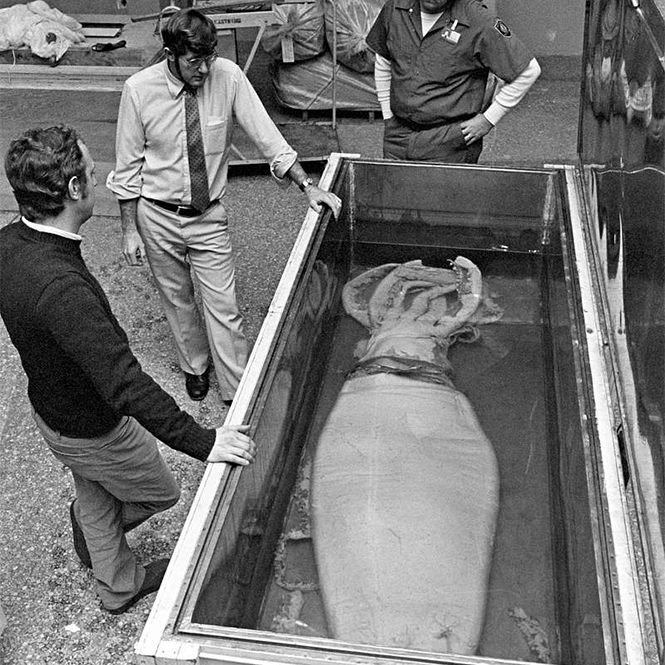

Michael J. Sweeney, left, and Clyde Roper prepare a

giant squid for display at the National Museum of

Natural History.

When it comes to separating the animal from the mythological beast known as the Kraken, Dawe admitted that there has been plenty of work done in the zoology community to attempt to keep track of giant squids and their southern hemisphere cousins, colossal squids.

He pointed to the work of American zoologist Michael J. Sweeney, who cataloged the sightings of Architeuthis for the Smithsonian Institute in 1999.

But Dawe also noted that the giant squid could be the polar bear of invertebrates — a champion of biodiversity and conservation.

“We made the case that the giant squid because of its interest to the public,” he said. “It would make an excellent representative for conservation in our world — an emblematic species.”

In the Elsevier study, “The giant squid Architeuthis: An emblematic invertebrate that can represent concern for the conservation of marine biodiversity”, Dawe, along with three colleagues said:

“Architeuthis can represent concerns for vulnerable marine ecosystems associated with submarine canyons and that it belongs to a broad diverse phylogenetic group of organisms associated with these canyons, sharing common concerns with that group concerning vulnerability and conservation.”

Editor’s note: The interview with Earl Dawe was initially done for a book.