Canada’s westernmost province has a rich history of water monsters. There are those we know — the Pacific giant octopus, the white sturgeon, the orca whale — and then there are those that inhabit the folktales and urban legends of British Columbia: Ogopogo, Cadborosaurs, and Shuswaggi, among many others. One of the oldest and most frequently written about is the Stin-Qua of Cowichan Lake, a freshwater lake west of Duncan, B.C. Sightings of the massive, eel-like creature by settlers date back to the nineteenth century.

One of the earliest accounts of a sighting on Cowichan Lake dates back to November 17, 1885. The report claims that a man named Charles Morrow and his two companions took a canoe out onto the lake, where they encountered “an extraordinary object which quickly lifted its head out of the water, and continued to raise it until it was some 20 feet above the surface.” Described as having an “eel-like head,” the visible part of the creature’s body “resembled that of a gigantic snake, being of a reddish-brown hue on the back and a dull white star on the belly.”

The animal is referred to as the Stin-Qua (or Tsinquaw) after a local Indigenous legend, and sightings continued into the 20th and 21st centuries. Its heyday was likely during the lake monster craze of the 1920s and 1930s when newspapers throughout North America and Europe frequently reported on strange creatures spotted in lakes, for instance, the famous Nessie in Scotland. Researchers like Dr. Darren Naish have posited that films from that era, such as The Lost World and King Kong, depicted sauropod dinosaurs, some immersed in water, and people began either seeing such creatures or hoaxing them.

An article from the October 25, 1929 issue of The Evening Journal out of Wilmington, Delaware reported a sighting that quotes eyewitnesses describing “a headless monster twenty feet long,” that was apparently floating on the lake’s surface.

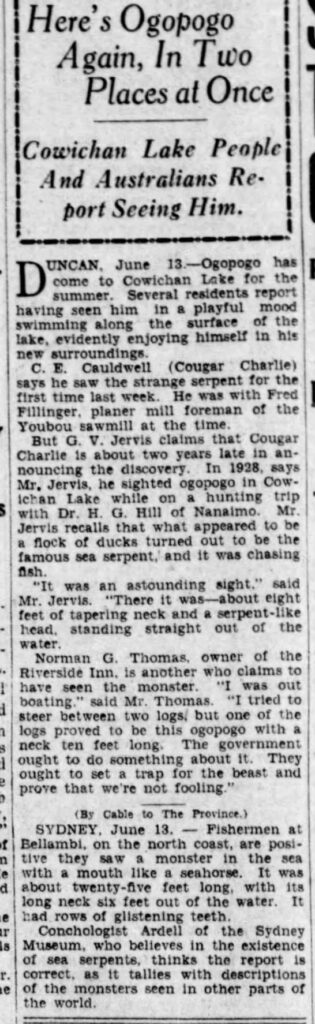

A June 13, 1930 issue of The Province details multiple eyewitnesses to another lake-dwelling monster, referring to it as “Ogopogo,” although far from Lake Okanagan. Eyewitness G.V. Jarvis said he saw “eight feet of tapering neck and a serpent-like head standing straight out of the water.” Another witness, Norman G. Thomas, describes mistaking the creature for a log on the water, claiming it had “a neck ten feet long.”

Such reports continue to this day. Coming back to Stin-Qua, Randy Stewart, a former resident of the area, described two encounters in recent years. The first was a solo encounter while kayaking and the second was when he was out on the water with his son.

“I was kayaking in the early morning, the water was calm like glass and suddenly the backend lifted up as if something big had just passed under me,” Stewart said.

Stewart, although “freaked out” by the incident with the kayak, did not conclude immediately that he had encountered Stin-Qua. It was only after both he and his son saw the creature in that same part of the lake that was he convinced.

“The year we saw it was the hottest in many years. The rivers were literally bone dry and the lake level had dropped significantly, the lake too was extremely warm and there had been a minor tremor that morning and a fishing derby in the morning,” Stewart said.

“In the end, I would have to say [it was] an eel-like creature … very large bottom-dweller that rarely comes to the surface.”

Cowichan Lake is the second largest lake on Vancouver Island. It is 30 kilometres long, four kilometres wide, and has a maximum depth of 160 metres. It is connected to the Pacific Ocean by the Cowichan River. Still, is the lake large enough to provide a home for a population of large eel- or snake-like animals unknown to science?

of The Province.

How might we determine if there was a large creature living in the depths of Cowichan Lake? Tracy Michalski, a Senior Fisheries Biologist for the provincial government has conducted extensive fieldwork in and around Cowichan Lake. Michalski has not seen Stin-Qua but has the expertise in this particular ecosystem to the point where one should look for this creature and what signs it might leave behind.

“I might expect it to follow its prey and leave signs because of those pursuits,” Michalski said. “The littoral zone or lake shoal is often the most profitable place for fish — especially at night — for example, Cutthroat trout will prowl this zone at night because juvenile fish are rearing there and, because they are vulnerable in full light, will be out feeding at night when it is safer.”

Cowichan Lake is considered oligotrophic, meaning it is nutrient-poor. Despite the speculations that the Stin-Qua might live in the depths of the lake, it would likely need to come toward the surface to find food, which would conceivably lead to more eyewitness accounts from the many anglers that fish in the lake.

“Cutthroat follow the Kokanee when they are spawning in the spring. If this animal is following the Cutthroat at that time toward the stream outlets of Nixon and Sutton Creeks then these tributaries might show signs of the animal having been there fishing,” according to Michalski.

“If this is the situation in the spring, you might also expect that Cutthroat derby anglers (there are many spring derbies) would see this animal as they would all be following and competing for Cutthroat.”

Not only might we expect more witnesses to such a creature given the human presence on the lake, but human activity makes it harder for the lake to sustain a creature like Stin-Qua. Not only has the number of anglers in the lake lowered the number of fish, but they have also affected the size of the individual fish, which already tend to be smaller there due to environmental factors such as nutrient-poor water.

“There are fewer large fish in a population than there are small fish. So, if anglers target large fish (and many do), they will reduce that segment of the population first. It is common in unfished populations that are open to angling that large fish will be cropped off first. Over time, the size distribution will shift toward smaller and smaller fish,” Michalski said.

Assuming that Stin-Qua is a predator, Cowichan Lake does not sound as though it hosts an adequate food supply to support a population of large eel- or snake-like animals. If the creature is herbivorous, the same problem applies as much of the vegetation along the shore of the lake has been removed by logging and development. The impact of this habitat loss has a ripple effect on the lake’s food chain: this vegetation provides a home and shelter to invertebrates, which make up a significant portion of the diets of many fish species in the lake.

Still, evolution is a wondrous thing, and there is at least one unique and somewhat mysterious creature known to reside in the lake. The Cowichan lamprey, an eel-like fish that is distinct to Cowichan Lake, is a fascinating example of evolution in isolation. Although monstrous when magnified, the Cowichan Lake Lamprey is far too small, about 273 mm, to be mistaken as the beast that terrified so many eyewitnesses.

It has been theorized that Stin-Qua might have been a remnant population of White sturgeon, a prehistoric-looking fish that can grow to over three metres from tip to tail. Others have suggested that the sightings could be rivers otters playing in a group, which, at a distance, could appear as one animal moving through the water like a serpent.

With any cryptid, there is likely no single explanation for every encounter, and nothing can be proven without evidence. We cannot disprove the existence of such a creature either, but only assume that it is unlikely such a creature exists in a lake with so much human activity and so little food source for as large an animal as Stin-Qua. Still, no one can say for certain what is or is not swimming in the depths of Cowichan Lake.

The author would like to thank Tracy Michalski, Research Fish Biologist for the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations & Rural Development, and John Kirk from the British Columbia Scientific Cryptozoology Club for their assistance in providing research material for this article, and Randy Stewart, for coming forward about his encounters at Cowichan Lake.